CALIFORNIA LAWYER NOVEMBER 1997

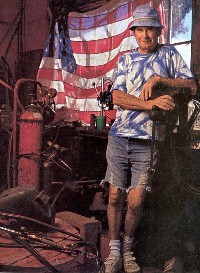

ENTANGLED IN A CLEANUP DISPUTE, THE OWNER OF A BERKELEY AUTO BODY SHOP TOOK ON HIS INSURANCE COMPANY AND WON.

By Carla Norton

Photograph by Mark Estes

With Vann v Travelers soon to be heard by the First District Court of Appeal, that future may be at hand. For the past repaired, seven years Vann has been a pawn in a complicated and con- tentious environmental battle, which began when he'd just started to prepare for a quiet retirement. These plans unraveled when his longtime friend Harry Williamson passed away.

It's always hard when an old friend dies; it's worse when that friend happened to be your landlord, and his son who inherits the estate no longer wants you as a tenant. Vann's Auto Body Shop, Inc. had thrived in Berkeley for close to 40 years. Customers brought in their classic cars for painting and polishing.

Vann recalls one customer who shipped his Rolls-Royce all the way from Texas to be repaired and Vann still takes pride in the custom aluminum body cars that he says "we built from the ground up." With the auto shop well insured Vann figured he'd provided for any contingency. At age 70 he dreamt of drifting off into retirement aboard his own fishing boat. But in 1991 Vann's business faced eviction and a lawsuit from his landlord alleging that paint and sanding dust had left a toxic residue on the property and that he had improperly disposed of oils, solvents, and other materials, contaminating the site.

Vann turned to an acquaintance, Thomas J. Titmus, a Lafayette-based attorney.

These cases raise the difficult legal and financial question of who is responsible for environmental contamination. Answering this question often requires thousands of dollars to trace the line of causation and then pay for the experts to explain it to a jury. It only gets messier when the litigation then turns to the issue of who shells out the money.

With millions of dollars often required to do the cleanup, just what are an insurance company's obligations? And if a company decides it has none, what recourse does someone like Gordon Vann have?

Vann's Auto Body occupied one of three adjacent properties housed under a single roof. (The other two were also occupied by small businesses, Berkeley Glass and Bauer's Import Car Repair.) The new landlord, Bruce Williamson, hoped to sell the three lots to Berkeley Repertory Theater, which abutted the property. As part of a due diligence investigation required by the lender, the theater hired contamination consultants, who found that Williamson's property was contaminated, with some potential for groundwater pollution.

Williamson's legal team hired its own experts to prepare a hazardous materials study of the property. After confirming the property was contaminated, Williamson's attorneys served Vann with an unlawful detainer action to evict property at 2015 Addison Street. They also filed a complaint for damages, including cleanup costs of approximately $150,000. (Since Vann's Auto Body had once occupied 2011 Addison Street as well, having polluted that property, too.)

Vann quickly discovered that environmental contamination cases are expensive, highly specialized, and require many experts. Williamson had plenty of experts working with his legal team, but Vann could barely afford to pay his attorney. In a letter to Vann, Titmus warned, "You can see now that the plaintiff and his attorneys are intent upon making this a very costly operation to you as well as to themselves."

Titmus thought Vann had a strong defense: Vann had records proving that he'd properly disposed of hazardous wastes through a recycling company (any contamination,Vann maintained, was due to accidents). But Vann fell several months behind on his legal bill, and in February 1992 Titmus decided to withdraw from the case. Vann was left to represent himself It was a bad start to a bad year. Evicted from the propertyVann had to take out a loan to pay the price tag for moving his body shop. Business was slow, bills mounted, and Vann defaulted on his payroll taxes.

Vann hired a tax specialist to help him work out a payment schedule to pay the $73,000 he owed the IRS. If things were bleak at work, there was no reprieve at home---Gordon Vann's wife was suffering from a syndrome related to Alzheimer's. Though she needed the help of a caregiver, the couple simply couldn't afford it. Finally, the deluge of legal documents became overwhelming, and Vann went in search of another lawyer. Early in 1993 a knowledgeable friend recommended a young, soft-spoken environmental attorney whose placid demeanor belied a fighting spirit. Leandro H. Duran, a sole practitioner then located in San Jose, didn't know that the was about to augment his environmental expertise with a large measure of insurance law.

| Soon after accepting the case Duran asked Vann about liability coverage Vann explained that his insurance agent had been unable to locate his policies. Thinking that Titmus's legal letter-head may have seemed threatening, Duran suggested that Vann make a personal request. |

Duran was confident Vann had an ironclad case. In July 1993 Duran sent a letter to Travelers outlining the case and urging them to contact him, as the trial date was fast approaching. There was only one potential stumbling block. The policy issued by Travelers covered the "discharge or escape of irritants, pollutants or contaminants," but only if the discharge was "sudden and accidental."

Travelers responded with a letter from Gregory Wank, an associate account manager with its Special Liability Coverage Unit (SLCU), who wrote that the SLCU needed thousands of documents dating back more than three decades before it could determine whether a defense obligation existed. Wank required an enumeration of all chemicals used at the site over a 33-year period with monthly volumes for each, the names and addresses of all personnel responsible for the storage of virgin chemicals and waste materials, as well as various other documents.

Duran considered these demands burdensome and largely irrelevant. Over the next several weeks he repeatedly urged Wank to send a Travelers representative to his office to review his files and interview Gordon Vann. Wank responded by reiterating the SLCU’s demand for stacks of records. (Travelers later admitted at trial that it needed only two documents, the claim and Vann's policy, to determine whether it had an obligation to defend Vann. By August 1993 Wank had both these documents.)

Still, Duran couldn't get a definitive answer. He says his invitations to settle the matter were at first accepted and then rejected, his letters seemed to have no impact, and his phone calls were not returned.

Then the California Supreme Court weighed in with a landmark environmental insurance coverage decision that Duran thought would squelch any lingering doubt whether Travelers had to provide a defense for Vann. In Montrose Chemical Corp. v Superior Court (1993) 6 C4 287, the court not only reaffirmed an insurer's duty to defend in an environmental context but also determined that normal and long-standing business practices in handling hazardous materials did not rule out the possibility of contamination from accidental causes.

In light of Montrose, Duran wrote a letter to the insurance company urging it one more time to take on Vann's defense. After two and a half months of non communication and without any mention of the Montrose decision, Wank sent a five-page letter stating that Travelers had no obligation to defend or indemnify Vann's shop. Wank cited numerous ways in which Vann's policies did not apply, noting that any alleged property damage was not covered. He also stated that Vann had failed to notify Travelers in a timely manner and that Duran's letter of July 19, 1993, did not meet the requirement of " ... immediate receipt of legal papers as defined in the policies issued to Vann's."

Citing from allegations in Williamson's complaint, Wank also maintained that the contamination of the property was the result of daily operations, not from causes that would be covered under Vann's policy. Specifically, the "discharge or escape of irritants, pollutants or contaminants" would be covered only if the discharge was "sudden and accidental." Finally, Wank "a business accommodation, a settlement offer in which Vann's will agree to relinquish all claims against The Travelers" in exchange for a settlement sum of $15,200.

Duran says he was "utterly shocked" by Wank's letter. He was surprised that Wank had raised the "sudden and accidental" issue, yet ignored the Montrose decision. And though Duran had urged Travelers to undertake some investigation of Vann's case, and had even sent photocopies of his entire file, Wank seemed to rely almost entirely on the allegations in Williamson's complaint to determine whether Travelers had an obligation to defend Vann. Furthermore, Duran believed the 1991 notification sent to Travelers' agent, Insurance Associates, was de facto notice to Travelers.

Taking Duran's advice, Vann rejected Travelers' offer. And in December 1993, convinced that the law was on Vann's side, Leandro Duran filed a declaratory relief action against Travelers, asking the Alameda County Superior Court to rule that Travelers had a duty to defend Gordon Vann.

Meanwhile, the underlying lawsuit, Williamson v Vann, was moving right along. In April 1994 Williamson's attorneys offered to settle the matter for payment fi-ornVann of $200,000, plus costs. But Gordon Vann's pockets were empty. He couldn't pay his mortgage, let alone his attorneys fees. (He was working on Duran's car as partial payment.) He defaulted on his tax payments and then received notice from the IRS that the agency intended to padlock his business. Duran advised him he had no option but to file for bankruptcy. Consequently, the IRS put a lien on Vann's house. The plaintiff’s demands continued to rise, spiraling to $750,000, plus costs.

In the case of Vann v Travelers, expediency seemed Duran's best alternative. He filed a motion for summary judgment. So did Travelers. In August 1994, after hearing the cross-motions for summary judgment, Alameda County Superior Court judge Ronald M. Sabraw granted a summary judgment verdict in Travelers, finding "........there is no potential for coverage because the alleged contamination does not fit the definition of 'sudden and accidental' so as to take it out of the pollution exclusion.... "

Duran appealed. In October 1995 the California First District Court of Appeal reversed the trial court in a unanimous decision and called Travelers' position "surprisingly weak." 39 CA.4th 1610. Although the insured's alleged discharge of pollutants occurred over a lengthy period of time, "sudden" refers to the pollution's commencement, wrote the court, and does not require that the polluting event terminate quickly or have only a brief duration. It also said that the underlying suit filed against Vann contained vague allegations that were broad enough to raise the possibility that the alleged contamination fell within the policies' coverage. Hence, Travelers had a duty to defend.

The case was remanded back to the trial court, and Sabraw sent it to arbitration to determine attorneys fees. Vann submitted a stack of bills, noting that he urgently needed to avert foreclosure on his house; his mortgage was more than $20,000 past due, and the bank was demanding $8,000, claiming it would foreclose by Christmas week.

Travelers advised Vann it would provide for his defense and his new attorney, James T Wilson of Crosby, Heafey, Roach & May, an Oakland firm specializing in environmental and toxic defense. (Duran withdrew when Travelers refused to pay his rate of $225 per hour, offering him S 150.) With the trial date a mere two months away, it was, Wilson recalls, "certainly the eleventh hour." Wilson adds that Williamson's attorneys were now demanding "slightly over a that million dollars:'including damages and attorneys fees.

|

With the help of two of the firm's lawyers, four outside experts, and a paralegal, Wilson made a successful motion to reopen discovery and disclose the experts, then quickly settled Williamson v Vann for a mere $50,000. Travelers paid Wilson's fees, it paid for experts, and it paid the $50,000 settlement. But that's where it drew the line. Travelers refused to pay thousands in outstanding legal bills. |

Philip Pillsbury flew to Hartford, Connecticut, to take the depositions of Gregory Wank and Mark Van Vooren, vice president and the head of the Special Liability Coverage Unit for Travelers. During eight days of depositions Pillsbury learned a great deal about the SLCU, which had been formed in the mid-1980s to exclusively handle environmental claims. Pillsbury was astonished to hear Van Vooren insist in a deposition that the decision by the California court of appeal was wrong. Van Vooren also stated that if Vann's claim were resubmitted today, he would deny it again. "That was when we knew we had a big case:' Levinson recalls. was something very strange about the SLCU. Though environmental cases are notoriously complicated, there was no documentation of Vann's case, no paper trail to illuminate the paths of their decision making. Moreover, in his deposition Wank said during his three years with the SLCU he could not remember ever granting coverage for a defense. While Levinson prepared for trial, Gordon Vann's health deteriorated. Years of fighting lawsuits had taken a heavy toll. In the winter of 1996, at 75, Vann suffered a heart attack and underwent triple bypass surgery. Living on Social Security and promises, Vann had to turn to his sister, who loaned him $25,000.

Worse, he'd had to ask his daughter for a loan, and she'd managed to scrape together $1,000. In January 1997, just days before his trial date, Vann received a "Final Notice" from the IRS, threatening to take his house if he didn't promptly send payment of $149,189.47. In January Vann v Travelers went before Alameda Superior Court judge Gordon S. Baranco and a jury. John Leland Williams and Craig Sterling of San Francisco's Sormenschein Nath & Rosenthal represented Travelers. At the plaintiff's table, Philip Pillsbury sat with Gordon Vann. At stake was the bad faith claim-Pillsbury had the burden of proving that Travelers' decision to decline coverage for the lawsuit filed against Vann by his landlord was unreasonable. In his opening statement Pillsbury recounted Vann's long legal ordeal. He said Travelers' conduct had been reprehensible, that it had employed improper standards and had used abusive and coercive practices in its dealings with Vann. Williams opened by itemizing the ways in which Travelers was not responsible to Vann, reiterating that notice to its agent was insufficient to impose bad faith liability and that Travelers received no evidence that the contamination was "sudden and accidental." Furthermore, he argued, Travelers' conduct was reasonable because once the court of appeal issued its decision, the company settled Williamson v Vann and paid for Vann's defense. Pillsbury called to the stand Robert E Campbell of Fitzgerald, Abbott & Beardsley in Oakland, who had drafted the landlord's initial complaint against Vann. Campbell testified that he'd found evidence of sudden, accidental, and unintentional events that could have caused the ground contamination. He cited sudden spillages and rupturing tanks of damaged automobiles, and he further explained that the building's roof leaked----sudden storms could have easily washed spilled fluids down the drains. Perhaps the most illuminating wit ness was Mark Van Vooren, whom Pillsbury called as a hostile witness. Van Vooren testified that with respect to Vann he never used or referred to Travelers' own Liability Claims Manual, which specifically addresses the company's duty to defend. It was for rookies, he explained. And though he was aware of the California appellate court's published decision that held the complaint raised the possibility that the contamination fell within the policies' coverage, he admitted he'd never read it. Furthermore, he stated that he personally disagreed with the case. After exhaustively questioning Van Vooren, Pillsbury called three expert witnesses to shed light on the SLCU's practices. Kurt W Melchior, a San Francisco-based attorney with Nossaman, Guthner, Knox & Elliott, termed Travelers' response to Leandro Duran's July 1993 letter "improper" and its demands for documents spanning three decades "absolutely unnecessary," "extremely inappropriate," and even "outrageous. " Quoting from Travelers' own manual, Melchior stated that Travelers had a duty to defend Gordon Vann and to do so with speed. Melchior said that Travelers used the manual "as a sham,"

He concluded that Travelers had violated the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing by giving Vann "the runaround" and by "toying with him. " Over Williams's strong objections the testimony would be prejudicial, Pillsbury next called Jordan S. Stanzler, a partner in the San Francisco office of Anderson Kill & Olick, a firm that regularly represents policyholders in insurance coverage disputes. Stanzler had authored numerous articles regarding insurance coverage, some focusing particularly on questions of environmental contamination. And he'd done a study of Travelers' history regarding its handling of pollution cases. Although the results of the study were not allowed into evidence, StanzIer had found that prior to the establishment of Travelers' SLCU, the company had a good record of defending cleanup claims. But after federal Superfund laws went into effect and the SLCU was formed, StanzIer had found that most claims were denied.

Although Stanzler's testimony was limited to his opinion on a few narrow points, he concluded the SLCU did not follow Travelers' own manuals and "the SLCU was set up to deny coverage." He further asserted that with the establishment of the SLCU, Travelers made a "180-degree change from what their practice had been over many, many years."

Pillsbury also called Bernard Martin, an expert on insurance claims handling whose credentials included 44 years in claims adjusting, underwriting, and consulting, with special emphasis on bad faith cases. Martin testified that in his opinion Travelers wrongfully refused to defend Mr. Vann, a refusal that he termed "unreasonable." He further opined that "Mr. Vann's request for a defense was approached [by Travelers] with the mind-set to deprive him of policy bene- fits.... There was never a serious thought of providing him a defense." On that note, the plaintiff rested.

In presenting Travelers' case, Williams called Vann's bookkeeper in an effort to prove that Gordon Vann's financial problems were of his own making. The records showed that Vann's IRS problems predated the suit and that Vann's that business was not profitable. Mark Van Vooren testified that contrary to the plaintiffs experts, the SLCU did not have a policy of denying coverage. Unlike Gregory Wank, who'd worked only three years with the SLCU, Van Vooren recalled numerous lawsuits that had been defended by Travelers, and he backed this up with statistics.

Wrapping up his argument, Williams made a motion to admit judge Sabraw's opinion into evidence. He argued it was unfair and prejudicial to include the court of appeal decision but not Sabraw's opinion. The motion was denied.

0n February 14, 1997, the jury sent a valentine to Gordon Vann. After a day of deliberations, the jurors awarded Vann compensatory damages of nearly $1.5 million. They also found the defendant had breached the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing and had committed oppression, malice, and fraud.

The judge then told the jury that the net worth of the defendant, Travelers Indemnity Company, was $2.4 billion, with a net income for 1995 of $299 million. That afternoon the jury awarded punitive damages of $25 million-the fifth largest recovery for an individual against an insurance company in California history.

Pillsbury and Levinson see Gordon Vann as a statistical anomaly, primarily because few policyholders would have fought so long and so hard. In their view, Travelers was counting on exactly that. Its "stubborn refusal to follow the law," Levinson says, was "a pre- designed course of conduct to avoid liability claims."

Travelers has filed an appeal. The case is set to be heard by the First District Court of Appeal, and the Insurance Environmental Litigation Association (an insurance-industry- lobbying organization based in Washington, D.C.) has filed an anticus brief in support of Travelers. In the appellant's opening brief, Travelers' attorneys take issue with the fact that judge Sabraw's opinion and order were not allowed as evidence. Moreover, the jury was never instructed on the tort of bad faith and was never explicitly told that it had to find that Travelers acted unreasonably.

Gordon Vann still feeds the ducks and geese near his dock twice a day. He still totters about in ragged clothes and does the best he can to care for his wife. And if he wins the appeal, he says he'll buy a fishing boat. He plans to name it Travelers.

On October 21, 1998 the time to file for a Writ of Certiori expired thus, Mr. Gordon Vann prevailed his action against travelers.